Last week, my first journal paper was published in the Journal of Medical Internet Research, on GPs’ concerns about online patient feedback. As a PhD student I was very pleased, I must admit it had not been the most enjoyable experience (I think most academics probably would not describe it as enjoyable!). However, now that my 1st paper has been published, I feel much more confident about writing and submitting more papers! I have also learnt a lot through that experience, and I thought I would share my 5 top tips to getting your 1st journal paper published:

1. Find the ‘right’ journal before you start writing your paper

This is one of the most crucial steps, not just because this will decrease the chance of you receiving a rejection (which would save you from feeling demoralised), but because if you publish your paper in the right circle, it is much more likely to be cited and used. It also means that the reviewers your paper is allocated to are much more likely to be people who have published in your very specific area and you have cited in your paper, and therefore are much more likely to give you useful feedback to improve your paper, and will are more likely to be receptive to your research and findings. I would highly recommend doing this step before you start writing the paper because this way you can write your paper and scope it to the format required by the journal paper.

So the question is – how do you know if a journal paper is ‘right’ for you? Firstly, have a look at the top 10 publications in your very specific area, and see if there is a journal that is most commonly published in. Once you have found the top/three journals in your area, see if those journals publish the type of research you are presenting (qualitative research for example is not published in the BMJ). Thereafter, check the journal’s citation report and impact factor on the Web of Science database. I think by this time you would have narrowed down your list to 1-2 journals. If you still feel unsure, email the journal’s editor with a very brief description of your article, asking them if they were likely to consider such a paper for publication.

2. ‘Revise and resubmit’ or ‘major revision’ is generally good news – don’t panic!

When I received the revise and resubmit decision with a long list of proposed corrections, my instinctive reaction was to panic. But do not panic. A revise and resubmit decision is usually good news because it means you have room for negotiation with the journal editor. I think it is extremely uncommon to get minor revisions only on a submitted journal, especially if it’s your first paper which has not been externally reviewed before. I would also recommend letting that email you receive sit in your inbox for 1-2 days – just to give you room to breathe and deal with more objectively, with less emotion.

3. Address and respond to all of the reviewers’ concerns methodologically

The first thing I would recommend doing is reading through it all, and then sorting out all the comments you have received methodologically so that it’ll be easier for you to address the reviewers’ concerns and make changes based on them. I decided to use the strategy mentioned here, and placed all the comments on a spreadsheet with columns such as Reviewer comment, Our response, Accepted or Rejected, Completed, Mentioned by another reviewer? This worked very well for me, however, when my supervisor checked them before I submitted the responses, he found altering them with track changes difficult to do in Excel. Therefore, next time round I would probably do them in Word. I have created a template that you could use if you wanted to place the comments you receive into a methodological order in both Excel and Word, and you can download them from here. Presenting them in this way meant that I could first correct the ones that were easy to do (like minor changes to language, or format), and then see which concerns had been repeated by reviewers, which meant I only had to address them once, and I copied the response over to where it was repeated. The format meant it was also easy for my supervisor to review and approve, and I also sent the document back to the journal, and the editor and reviewer may have used it too to see how reviewers’ comments had been addressed. Also, finally, do not forget to respond to ALL the comments, however trivial.

4. Use appropriate language to address the reviewers’ concerns

The more polite and courteous you are in your response to each of the concerns mentioned by reviewers; naturally this is going to be favourable to the editor and reviewers. Some comments may make you swear or angry, but it very important not to put that across to reviewers or the editor. I found this template very useful when I was writing the response to each of the reviewers’ comments. I also wrote the responses in the template above before or whilst I was making the changes, and edited them all lightly at the end.

5. Do not take feedback or rejection personally – feedback will only improve the quality of your paper

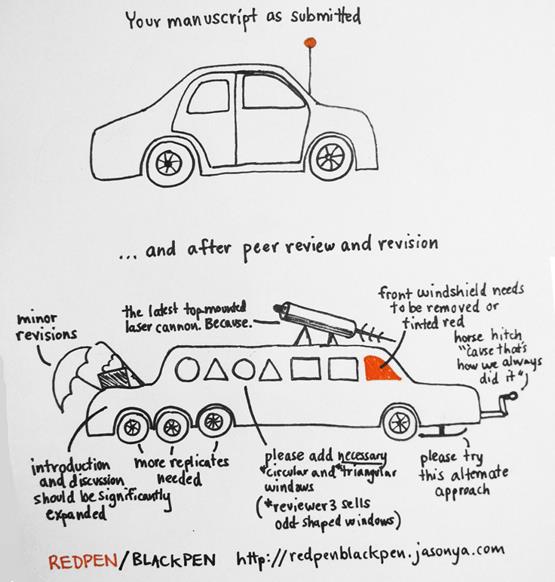

Although this is not an action tip per say, I believe this underpins some of the frustrations many researchers have with the whole publishing process. When you receive a very long list of corrections, sometimes up to 50 comments, it is easy to feel deflated, and one can start doubting their research skills (especially if you are an early career researcher). But I have heard from many experienced researchers that they also receive a long list of corrections/comments. So do not take it personally. Feedback, criticism, corrections, amendments, changes, whichever word you use to describe the reviewer’s comments, will only improve your paper (or at the very least help get it published!). I found this drawing to be true for my paper:

So, do you have any tips or advice on getting a journal paper published, especially for early career researchers? I would love to hear from you!

[…] (Post first published on salmapatel.co.uk) […]