Surveys are powerful tools to gather data, if used correctly. Recently, five people have asked me about evaluating or validating survey questions. This is the approach I use.

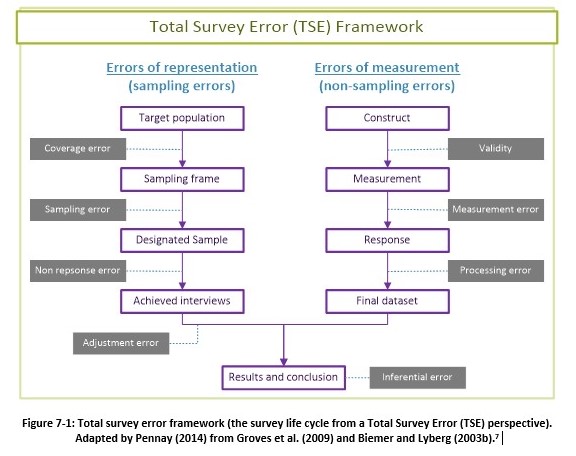

I use the Total Survey Error Framework (Pennay 2014) as the conceptual and practical framework to assess and reflect on improving the quality of the questionnaire and its results, and to reduce the possibility of any errors (Whiteley 2015). The framework (as shown below) consists of both errors of representation (sampling errors) and errors of measurement (non-sampling errors). The former occurs as part of the selection of the sample from the sampling frame. The latter occurs when designing and conducting the survey. All of these errors need to be minimised as far as possible in survey research.

I will focus in this post on the validity and measurement errors and how they can be reduced i.e. how can we ensure that the survey questions are valid and are really measuring what they intend to measure?

Validity refers to the extent to which a construct (elements of information sought by a researcher) is adequately captured; this is sometimes referred to as a specification error. This is usually a high-level error, whereas the measurement error is the extent to which a measure (for example a question posed to the respondent) accurately captures the construct.

The measurement error could be related to

- the questionnaire (poor questionnaire design),

- the respondent (they could provide inaccurate answers due to misunderstanding or not understanding the question)

- the interviewer (poor interviewing technique);

- the mode of the questionnaire (for example, primacy effects are more commonly associated with paper-based self-completion surveys).

The processing error refers to errors when inputting the raw data or computing new variables. This will be not be addressed here.

Steps to validate

To minimise the validity and measurement/observation errors of a survey, the following stages of evaluation should be considered:

1. Expert reviews

Groves et al. (2009) and other survey researchers recommend the use of ‘expert reviews’ as the first step to validate the questionnaire (DeMaio and Landreth 2004). Expert reviews are where both questionnaire design experts and subject matter experts evaluate the content, cognitive, and usability standards of a questionnaire (Groves et al. 2009). This can highlight any problems the questions and scales may have in relation to its scope for example, or the way the questions may be understood or perceived by its participants, and evaluate whether the questions are clear and easy for participants to understand and answer (DeMaio and Landreth 2004; Groves et al. 2009).

2. Cognitive interviewing

Cognitive interviewing is a process in which participants respond to draft survey questions, and are asked to reveal their thought processes at the same time (Farrall et al. 2012; Priede and Farrall 2011). The premise is that knowing these thought processes and cognitive understanding can help the researcher evaluate the quality of the survey questions and responses. Furthermore, it can reduce response error because it can help identify any difficulties or problems that cannot be identified through statistical methods (Miller 2011; Osborne et al. 2006; Willis 2004). According to Levine et al. (2005) and Willis and Artino (2013), there is a growing body of literature that demonstrates that only a very few cognitive interviews can allow for the identification of problems with questions, and help in making revisions, so that the quality of the survey data can be greatly improved.

Cognitive interviewing has evolved and grown since its first use in 1984, and now there are two ways cognitive interviews are conducted: thinking aloud and verbal probing (Priede and Farrall 2011). In the former, the respondent is asked to vocalise his or her thought process as he or she is filling in the questionnaire. The researcher then reads or listens to the transcript to understand the respondent’s thought process and understanding, and uses this to remove or change any difficult questions or phrasing. In the latter, the researcher takes a more active role, and respondents are probed with questions to get a better and deeper understanding of their thought processes.

I use the verbal probing method alongside the thinking aloud method to detect potential sources of response error. This is because when the thinking aloud method is used on its own, useful information is not always gained, since although it can highlight that there is a problem with a question, it cannot always tell you what the problem is. Furthermore, some participants may find it difficult to think aloud, and you may also want to focus on specific areas. For example, to check participants’ understandings of specific terms are correct and consistent.

An interview guide is created to conduct the interviews and interviews recorded.

Participants and interview procedure – I tend to use a purposive sample (for example, in one of my studies to ensure participants were from different age groups). Willis and Artino (2013) argue that as few as 5 or 6 participants can provide useful information to improve survey questions, and this has been true in my experience too. The interview is conducted in the same way as generic interviews are conducted.

Analysis of the cognitive interviews – Each recording of the cognitive interview was listened to and a summary was prepared in an Excel sheet, which contained a list of responses to the probes, and any other problems that could be identified. This determined whether the interview provided evidence of a ‘definite problem’, ‘possible problem’, or ‘no evidence of a problem’ in relation to each item in the questionnaire, which was followed by a written explanation of the reasons for this judgement (as done by Levine et al. (2005)). These summaries were then combined under each question, and based on that it was decided whether the question needed modification, removing, changing or leaving as it was. Any additional areas mentioned or discussed were also noted down.

In one of the surveys I conducted cognitive interviews for, 23 problems were identified from cognitive interviews alone, despite it being expert reviewed prior to that and them finding 13 problems which had been resolved.

3. Another round of expert review (optional)

I tend to send the survey out for another round of expert reviews, but this depends on whether the survey has been heavily modified since undergoing cognitive interviews.

4. Pilot testing the survey (may be relevant for face-to-face surveys)

Although pilot testing may be useful for face-to-face surveys, this should not be used as the only validating method. Pilot testing tends to be used more to help with predicting the analysis of a large-scale survey. For one of the face-to-face surveys I designed, the survey was piloted face-to-face with 22 volunteers, and the non-verbal behaviour of respondents was observed alone. This provided further information on any uncomfortable or difficult questions. For this particular survey, 12 changes were made as a result of piloting, despite the survey having undergone cognitive interviews and expert reviews prior to that.

5. Factor analysis (may be relevant for certain questions)

Factor analysis can be used to measure construct validity (how well your survey measures what is supposed to) where there are questions on the same construct or themes, answers of which when combined, more accurately answer an overall theme or question. Sometimes this overall theme cannot be measured accurately directly by asking one question alone. For example, say there are 20 different questions that ask similar yet different questions on whether you enjoy writing, and overall together they represent whether you enjoy writing (see page 2 on this document for the questions) . With factor analysis, you can measure whether which of the twenty questions measure the underlying construct (enjoy writing or not) well. Generally a fairly large sample size is needed to conduct factor analysis and access to statistical software too.

Summary

In order to validate surveys, there are two things to consider: sampling errors (not addressed here) and measurement/observation error (are the questions really measuring what we intend for them to measure?).

To minimise validity and measurement error:

Step 1: Send survey for expert reviews in to evaluate the content, cognitive, and usability standards. Expert reviews include a) subject matter experts in this area and b) questionnaire design experts. Once their feedback is back, make changes to your questions based on that.

Step 2: Conduct cognitive interviews using the amended survey. It is basically a think aloud method where the interviewer sits next to the person filling it in, and you ask the person to think aloud as they are filling it in, prompt them with relevant questions where appropriate (draft an interview guide to help). If you do a set of say 5 to start with, you would then analyse the results to see how people understood the questions and whether people are understanding the questions consistently and as we expect them to. If not, the question needs changing (and almost all the time, even survey expert’s questions need changing at this stage). You could then do another round of cognitive interviews if needed etc. till you end up with a survey that everyone is understanding in the very same manner and how you want them to.

Step 3 (optional): Do another final round of expert reviews, as described above or pilot testing if it is a face-to-face survey. If the survey has a group of questions that measure one overall construct/question/theme, consider conducting factor analysis.

Please note: Some of the text in this article has been taken directly from my PhD thesis.

References

DeMaio, T.J. & Landreth, A. (2004) Do Different Cognitive Interview Techniques Produce Different Results. Methods for Testing and Evaluating Survey Questionnaires. 89–108.

Farrall, S., Priede, C., Ruuskanen, E., Jokinen, A., Galev, T., Arcai, M. & Maffei, S. (2012) Using cognitive interviews to refine translated survey questions: an example from a cross-national crime survey. International Journal of Social Research Methodology. [Online] 15 (October), 467–483. Available from: doi:10.1080/13645579.2011.640147.

Groves, R.M., Fowler, J.J.J., Couper, M.P., Lepkowski, J.M., Singer, E. & Tourangeau, R. (2009) Survey methodology. 2nd edition. New Jersey, Wiley.

Levine, R.E., Fowler, F.J. & Brown, J. a (2005) Role of cognitive testing in the development of the CAHPS Hospital Survey. Health services research. [Online] 40 (6 Pt 2), 2037–56. Available from: doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00472.x.

Miller, K. (2011) Cognitive Interviewing. Question Evaluation Methods: Contributing to the Science of Data Quality. 51–75.

Osborne, R.H., Hawkins, M. & Sprangers, M. a G. (2006) Change of perspective: a measurable and desired outcome of chronic disease self-management intervention programs that violates the premise of preintervention/postintervention assessment. Arthritis and rheumatism. [Online] 55 (3), 458–65. Available from: doi:10.1002/art.21982.

Pennay, D.W. (2014) Introducing the Total Survey Error (TSE) framework.In: ACSPRI Social Science Methodology Conference. [Online] (November), North America, pp.1–17. Available from: https://conference.acspri.org.au/index.php/conf/conference2014/paper/view/768/58.

Priede, C. & Farrall, S. (2011) Comparing results from different styles of cognitive interviewing: ‘verbal probing’ vs. ‘thinking aloud’. International Journal of Social Research Methodology. [Online] 14 (4), 271–287. Available from: doi:10.1080/13645579.2010.523187.

Whiteley, S. (2015) Total Survey Error across a program of three national surveys: using a risk management approach to prioritise error mitigation strategies.In: ESRA Conference 2015. [Online] Ireland. Available from: doi:10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004.

Willis, G.B. (2004) Cognitive Interviewing Revisited: A Useful Technique, in Theory? Methods for Testing and Evaluating Survey Questionnaires. [Online] 23–42. Available from: doi:10.1002/0471654728.ch2.

Willis, G.B. & Artino, A.R. (2013) What Do Our Respondents Think We’re Asking? Using Cognitive Interviewing to Improve Medical Education Surveys. Journal of graduate medical education. [Online] 5 (3), 353–6. Available from: doi:10.4300/JGME-D-13-00154.1.

Comments